work / SCAPE 8: NEW INTIMACIES 2015

SCAPE 8: New Intimacies

Curated by Rob Garrett

Christchurch, New Zealand

October 3 - November 15 2015

New Zealand's premier Biennial of art in public space.

Media/Press for SCAPE 8: New Intimacies

Artist's announced for SCAPE 8: New Intimacies 2015 LINK

A conversation with Peter Atkins by Laura Thomson OCULAR Sept 24 2015 LINK

New Christchurch sculpture turns roadwork signs into art Charlie Gates, THE PRESS, Christchurch Sept 19, 2015 LINK

What's on this week around the world The New York Times, Oct 9th, 2015 LINK

Rediscovering our landSCAPE Warren Feenety, THE PRESS, Christchurch Oct 12 2015 LINK

Australian artist Peter Atkins was one of 7 artists invited to create new site-specific public art works for the forthcoming Christchurch Biennial, SCAPE 8: New Intimacies, curated by Rob Garrett. An important figure in Australian contemporary art, Peter Atkins has exhibited extensively both in Australia and internationally and is represented in the collections of every Australian State Gallery as well as prominent Institutional, Corporate and Private collections both nationally and internationally.

Ocula spoke to Peter Atkins on the occasion of SCAPE8 about his new work Under Construction—Chaos and Order.

SCAPE 8: New Intimacies represents the second iteration of the Biennale since the devastating earthquakes in 2011. How was the experience of working in Christchurch – a city still very much in recovery? My initial site visit and tour of the city by curator Rob Garrett was at times overwhelming and brought back terrible memories and images of the Newcastle earthquake, which I experienced along with my family and friends in 1989. This experience helped give me an insight into how residents were affected by the stress and turmoil. The sense of loss, confusion and disruption was palpable. However, I also knew that in time, as with Newcastle, a stronger city would emerge. Humans are surprisingly resilient to natural disasters. Biennial curator, Rob Garrett, has spoken about SCAPE 8: New Intimacies in the context of people forming new, memorable and intimate connections with the fabric of the city. What is your view on the role of art, in encouraging imagination and hope in the necessary process of recovery and healing? I’m particularly interested in opening up challenging dialogues between the audience and the artwork. I’m hoping the work will act as a memory trigger, eliciting from the viewer various emotional states or reactions, provoking memories around the idea of loss, what was, what’s missing, lost elements of the city, perhaps also allowing a platform for a shared optimism for the future, the possibility of happier or easier times ahead. There appeared to be an undercurrent of these emotional states prevalent throughout the community of Christchurch on my first visit. It is an important aspect of this work that it relates to these states as well as the current dislocated landscape. My work attempts to provide a positive engagement with contemporary abstraction by metaphorically carving out a space for the audience to add their own narratives. Quoting your interest in ‘taking seemingly ordinary elements of our day-to-day surroundings and re-presenting them thereby challenging perceptions and offering new ways of interpreting ones surroundings’, there are obvious connections between your work and the theme of the Biennial, New Intimacies. Tell us about what you have created for SCAPE 8: New Imtimacies? The conceptual framework of this proposal centers around the theme of ‘Sightlines’ as outlined by curator Rob Garrett in New Intimacies. The work is titledUnder Construction—Chaos and Order and is situated on The Press site along Gloucester St, between Manchester St and Colombo St. The work is double sided, so lends itself to being read from two vantage points, offering the possibility of entirely different readings of the one work. I’ve appropriated and deconstructed a series of common ‘lane management’ road signs unique to New Zealand. They are white with orange angled forms that suggest spaces within the landscape, possibly work sites under construction or being demolished. Large black arrows on the signs (which were later erased on the final work) alert and direct drivers around these hazards as they navigate the city. These signs were ubiquitous throughout the center of Christchurch when I made my first site visit in mid 2014. On one side I’ve arranged eighteen pairs of deconstructed signs in a random pattern that suggests a state of disorder or chaos – the city collapsed. The orange forms suggest rooflines, chimneys, roadways, city blocks etc. The fragmented pattern also implies obstacles, shards, dead ends and blockages - alluding to feelings of uncertainty, confusion and frustration. The opposite side of this sculpture however, is much more optimistic and signals the future rebuilt city center. The signs are arranged as an ordered, organized, methodical structure. This logical arrangement of patterns and the implied state of being ‘in control’ are what humans aspire to. However, this side of the sculpture will, I suspect, mostly be viewed by drivers in their rear view mirrors, or by passengers as they turn to briefly glimpse the work as they leave the area. The ‘sightline’ from this position implies that this goal is slightly out of reach, an ideal or something to aspire to – perhaps the future rebuilt city. As well as responding to the lane management signs you encountered in Christchurch, I understand you also made reference to the work of both Colin McCahon and Rosalie Gascoigne when developing the project? Yes, it is impossible not to reference Rosalie Gascoigne when working with roadsigns and clearly she has been a major influence on this work and throughout my practice. Robert Macpherson is another artist who has influenced my work at various stages. All three of us share a deep affection for the Australian landscape and in particular, the vernacular of highway road-signage within Australia. Conceptually though, we all approach the form and narrative from different angles. However, when I first saw the signs they also reminded me of my first experience seeing the work of Colin McCahon, the series is titled Angels and Bedfrom 1976-77. These works, painted on a black ground have various white triangle and square forms entering the picture plane, some from the side and others from the corners. The works from this series were painted after various friends of McCahon’s had become ill. The painted forms variously represent a room with a bed and Hi-Fi speakers. The forms could also be interpreted perhaps, as others have suggested, as protective angels watching over their charges. These powerful works, based around ordinary, everyday circumstances, remain some of my favourite images from contemporary art and are loaded with universal feelings of memory, concern, sorrow and loss. It seems appropriate within my practice to build upon and combine these and other personal narratives, (including those of New Zealand born Gascoigne and to a lesser extant Macpherson) when formulating ideas for this work, especially considering the context of the site within New Zealand. In my opinion the best art is made up of dialogues between other artists… voices joined together…no one exists in a vacuum; it is these multi-layered connections to memory and experience that underpin my practice. This new work for Christchurch had its genesis in a much earlier work of mine titledHume Highway Project, and is, in many ways, an extension of that project. Ultimately, the work should stand on it’s own, though perhaps on this occasion, it’s on the shoulders of giants...It is interesting to think about how the work will be encountered by the public. Installed on the street, it exists outside of the traditional ‘white cube’ providing viewers with the opportunity for a truly individual experience of the work – on their own terms. Were you thinking about this when making the work? Yes. An artwork sited within the landscape is in many ways free of the expectations and confinements of a gallery space. As you say, viewers either engage or not on their own terms. I am not necessarily interested in provoking negative reactions with this work, though it does have that capacity, instead, I am hoping that during the daytime the work will stand quietly in the cityscape, allowing the viewer to quietly contemplate, gently eliciting memories, evoking emotional states and personal narratives. At night when fully lit, the work will become a beacon in the darkness, drawing people in, simultaneously becoming a memory of place and a marker for the future rebuilt city. The specific siting of the work ensures that it will be seen from many vantage points throughout the inner city offering various levels of engagement with the viewer. Tell us briefly about the production. I understand that you wanted to produce the work in collaboration with local manufacturers of road signage and that you intended for local road workers to install it. Why was this was important to you and if in the end you were able to do so? The work is essentially a contemporary reworking of existing road signage. I didn’t want to step outside the existing vernacular, it was important for me to use the exact same processes and materials to fabricate the structure from the ground up. The engineering, manufacture and installation were all done in house with the team from Fulton Hogan. It was an overwhelmingly positive experience for me to work alongside these people; they embraced the project from the very first meeting. Ultimately, I wanted these workers, many of whom may never have had access to contemporary art, to claim a sense of ownership, to feel proud of their engagement with the work. It is after all, a sculpture for the people of Christchurch, so it’s appropriate that they physically build it as well. (O)

checking the prototype panel - St Asaph Street, Christchurch 2015

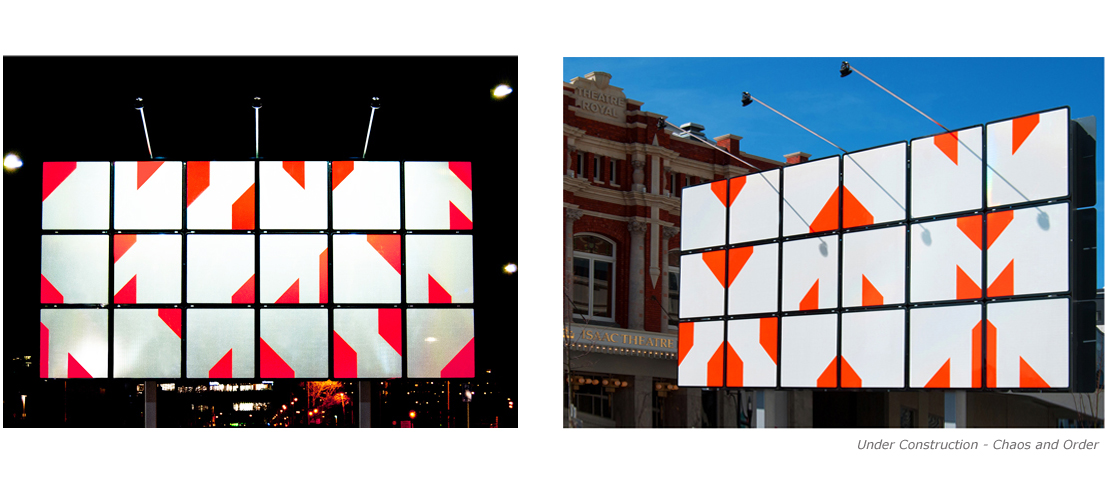

Under Construction - Chaos and Order

Kirsty Grant

When I think of the way Peter Atkins works, I am reminded of the great natural historians of the nineteenth century who sought to understand the world around them and the complex relationships that existed within it by looking, collecting, categorising and classifying the specimens they found. Through this process of documenting similarities, identifying patterns and defining difference, they established a rich resource of physical and visual material that provided the basis for their own scientific inquiry and much subsequent understanding. Similarly fascinated by the surrounding world, Atkins looks intently, collects relentlessly and sorts, finding order and variation. His focus is however firmly on the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and the man-made specimens that are mostly overlooked as ubiquitous elements and detritus of the everyday urban environment.

Atkins describes his practice as ’readymade abstraction’. Appropriating designs drawn from sources as diverse as product packaging, highway road signage and mid-twentieth century jazz album covers, he pares back extraneous details – typically removing text and any representational imagery – and reduces it to an abstract composition in which line, form and colour exist in a finely calibrated visual harmony. Atkins’ art is deeply rooted in the history of Modernism and various strands of twentieth century art. Within this he identifies in particular the influence of Minimalism and its drive towards an aesthetic simplicity, Pop Art and its co-opting of commercialism and re-presentation of the mass-produced object, and the post-modernist practices of appropriation and deconstruction, all as being significant within his approach.

Being based on designs drawn from the flotsam and jetsam of the everyday, Atkins’ unique brand of abstraction involves an element of familiarity – albeit one that is not immediately or easily identifiable after it has been transformed in his hands ¬– that successfully counteracts the struggle most viewers experience when looking for meaning in pure abstraction. This focus on familiar forms and shared cultural references injects an element of humanism into the work, giving it a broad relevance that evokes individual memories and experiences, and opens up the possibilities of personal meaning and narrative being ascribed to it.

There was an element of synchronicity at play when Atkins visited Christchurch in mid-2014 in preparation for his commission as part of the SCAPE 8 Public Art Christchurch Biennial. Being driven in a taxi from the airport through the city’s centre he was confronted by the physical realities of a city recovering from the devastation of the 2011 earthquake in which almost two hundred people were killed and more than half of the buildings in the CBD were brought down or subsequently demolished. [1] One of the first things that caught his eye from the taxi was a distinctive road sign, a combination of black directional arrows and angular orange forms against a reflective white ground. Hurriedly taking a photograph from the taxi, Atkins would later discover the sign was one of a series of lane management signs used to direct the flow of traffic around buildings under repair and construction throughout the city. These signs are unique to New Zealand and while the individual elements of the graphic language were familiar to the Australian-based artist, he was fascinated by the variation they presented when the series of eighteen was fully documented and collated.

As part of this visit Atkins travelled to Oamaru in Otago, where New Zealand’s pre-eminent modernist artist, Colin McCahon, was born. Moved by the landscape of the region, which he recognised from the colours and forms of the artist’s paintings of the subject, Atkins also recalled the Angels and Bed 1976-77 series, large works on paper that had been his first experience of the artist’s work many years before. [2] McCahon made these works, which utilise a series of black and white linear and geometric forms, to describe the rooms in which he had visited sick and bed-ridden friends, and it was this recollection which drew together various strands of Atkins’ experience, including a visual connection between McCahon and the road signs, at which point the conceptual framework of his commissioned public sculpture began to emerge.

Making art based on road signs was not entirely new to Atkins who, in 2010 had produced a major series entitled the Hume Highway Project. In this work the road signs along the Hume Highway between Melbourne and Sydney were transformed into abstract paintings, familiar to anyone who has ever driven that route and yet, devoid of all text and graphics, quietly elusive. Other artistic precedents also came into play – from Robert Macpherson and his monumental paintings based on the rough and ready hand-painted signs that advertise rural produce along many country roads, and Rosalie Gascoigne, whose collages of retro-reflective road signs have come to define the subject. The influence of these diverse sources on the final realisation of Atkins’ work are subtle however, as his unique aesthetic comes to the fore and familiarity, however indefinable, prompts the layering of individual memories, experience and meaning across the work.

Under Construction – Chaos and Order, Peter Atkins’ commission for SCAPE8 presents a double-sided sculpture that utilises the essential materials of a roadside sign, as well as adopting its basic form. The lane management signs have been reduced to a series of white squares intersected by a variety of triangular and shard-like orange forms and arranged in a 3 x 6 grid. Located on Gloucester Street, the work is visible from both sides and it is here that the binary opposites of the title come into play. The chaos of one side is the result of the deconstructed signs having been arranged in a random way that sees the orange forms scattered haphazardly across the surface, as if they have been tossed into the air and left where they fell. This apparent lack of order is countered on the reverse by a more controlled configuration in which the mirroring of the orange forms across adjacent signs produces a series of arrowhead shapes suggesting logic, order and signalling the way ahead.

In making this piece Atkins wanted to work within the existing vernacular of roadside signs, collaborating with engineers, manufacturers and a local installation crew and utilising exactly the same materials and processes to fabricate and install the signs. It is through these means that the work will challenge and surprise, as both local residents and visitors to Christchurch, realise that the sign they just drove past is not just a sign and stop to look again. Although Atkins’ visual language is abstraction, his is an art that seeks to engage the viewer through the re-presentation of familiar elements and through this, to provide a space in which they can interpret the work and create personal narratives around it.

[1] http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/page/christchurch-earthquake-kills-185, accessed 20 September 2015

[2] Atkins saw the Angels and Bed series in the stockroom at Martin Browne Fine Art, Sydney.

Images can also be viewed as a slideshow - LINK

SCAPE 8: New Intimacies - CHRISTCHURCH - reference forms for 'Under Construction - Chaos and Order' 2015

SCAPE 8: New Intimacies - CHRISTCHURCH - reference forms for 'Under Construction - Chaos and Order' 2015

SCAPE 8: New Intimacies - CHRISTCHURCH - Maquettes showing both sides of 'Under Construction - Chaos and Order' 2015